The "Corporate Campaign" Strategy

Helping Labor Unions and Public Interest Groups Confront Unbridled Corporate and Political Greed since 1981

Learn More

Helping Labor Unions and Public Interest Groups Confront Unbridled Corporate and Political Greed since 1981

— Download Article —

The 14,000 member Local 1-2 represented hard-hat and office workers at the giant New York City utility, Consolidated Edison. It was one of the most internally divided and politically fragmented unions for which Corporate Campaign, Inc. has worked. The unions numerous factions were all trying to undermine each other rather than march together in solidarity. Even among the most activist members, moral was plunging to an all-time low. Five years earlier, dispirited members suffered through a nine-week strike that basically left them hanging out to dry.

In an early edition of The Record, Local 1-2's newspaper, the union's new business manager emphasized: "Management believes, deep down, that we are divided and weak. They believe that we have not recovered from the 1983 strike and that the division which has plagued our union since then will keep us from uniting as one this year... With contract negotiations around the corner, we have been gearing up for one of the biggest fights our local has ever had. For the first time in the history of our local, we have embarked on a six-month campaign before the contract expires."

Truck with supporters of UWUA Local 1-2 including Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins, City Council Member Ruth Messinger and Local 1-2 Business Manager Gene Briody

The front page and a special centerfold pullout section highlighted CCI's research and showed members that their fight was not just against Con Edison, but an intricate web of very powerful New York City-based financial institutions. Surveys showed that most Local 1-2 members and/or someone in their families had bank accounts and insurance policies with companies and shopped at retail outlets of companies connected to Con Edison. Hundreds of other unions also had business relationships with the financial institutions intimately connected to Con Edison through directorate interlocks, and stock or credit relationships. For example, two of Con Edison's 14 directors were the former CEOs of Metropolitan Life Insurance and Con Edison. Both of these men still served as directors of Metropolitan Life. Metropolitan Life also held a chunk of bonds and stock in Con Edison. Similarly, New York Life Insurance's CEO served on Con Edison's board and the company held more than $100 million of the company's bonds. Furthermore, two of New York State's largest pension funds covering tens of thousands of unionized state workers had large investments in Con Edison.

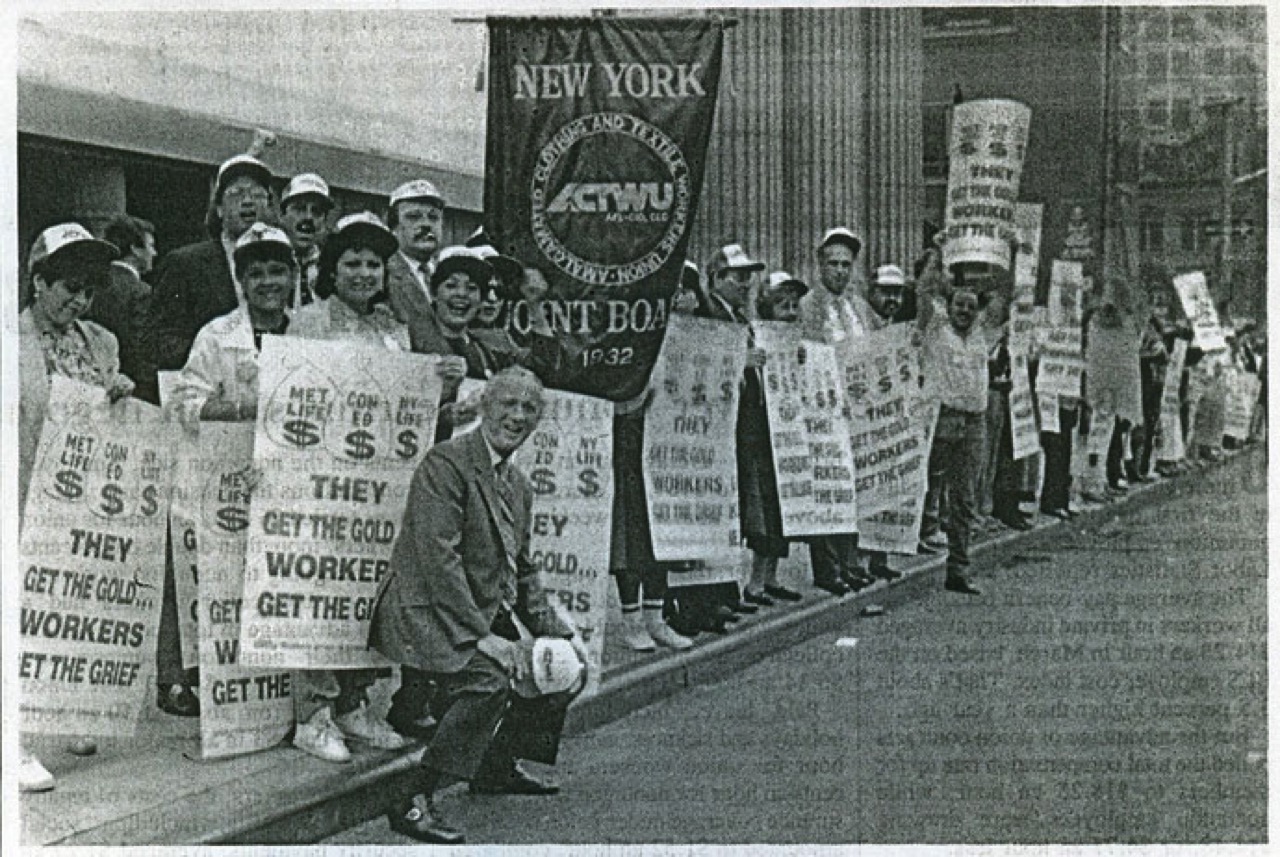

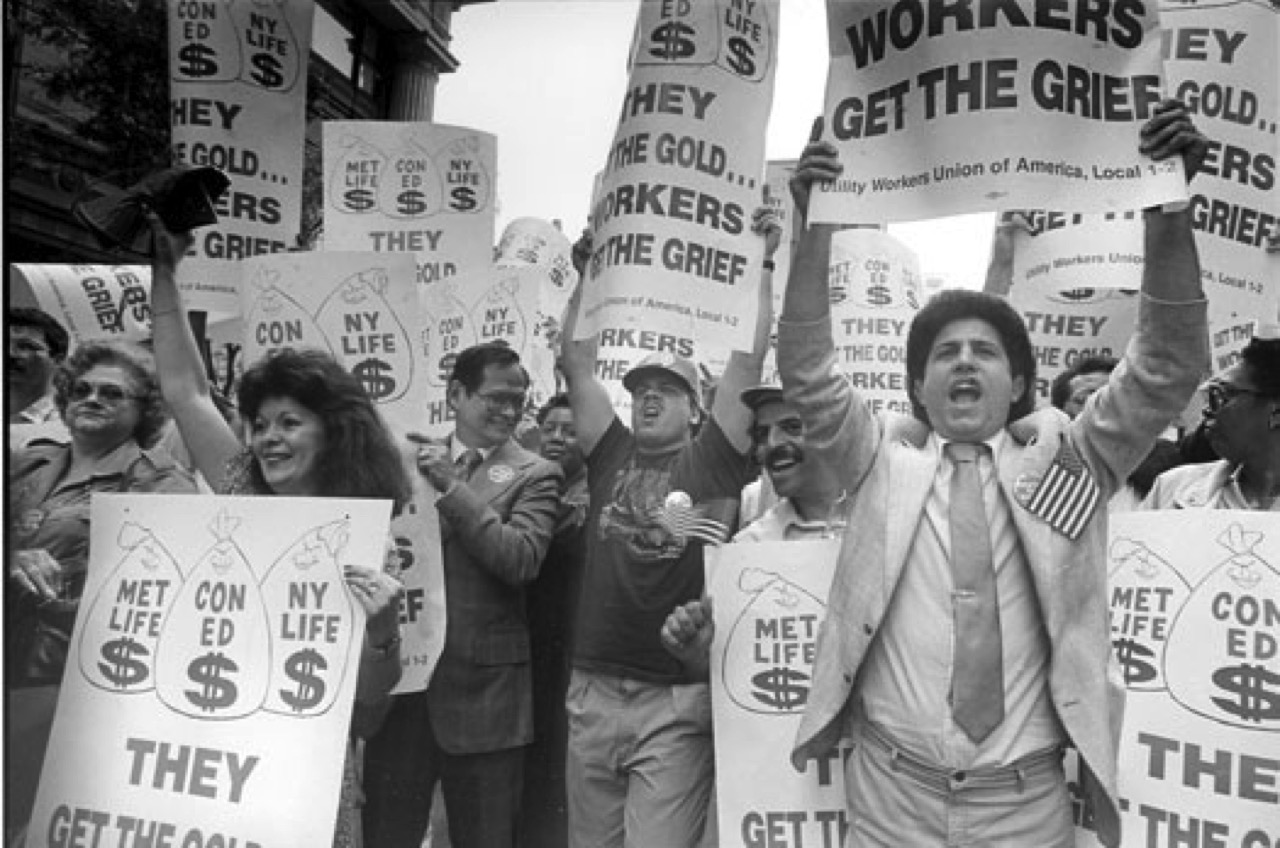

Section of the "Mile Long Human Billboard"

As the local focused on communicating with and involving the membership, CCI challenged the leadership to organize a "Mile Long Human Billboard" solidarity demonstration. CCI Director Ray Rogers told Local 1-2's executive board that if the union's political factions couldn't get their act together and pull it off, then they wouldn't be ready to successfully challenge Con Ed. A few top-ranking city labor leaders urged Local 1-2 to scrap the idea, saying it won't work and the union will look bad and be embarrassed. Some of these same city labor leaders had to acknowledge afterward that the demonstration was one of the most significant labor actions in New York City in 50 years.

— Download Article —

Such a demonstration demanded precise timing and a high degree of organization since thousands of protesters had to be on assigned blocks with signs and banners for half an hour at lunch time on one of New York City's busiest avenues during peak traffic. Protesters, three and four deep on many blocks, crowded together shoulder-to-shoulder displaying banners and large placards saying, "They (Met Life-Con Ed-NY Life) get the gold, workers get the grief." The "human billboard" surrounded the entire city block at Park Avenue and 27th Street (New York Life headquarters), extended down to Park Avenue and 23rd Street (Met Life headquarters), where it again completely surrounded the block, and turned the corner to Irving Place at 14th Street, surrounding Con Edison's headquarters. Thousands of sign-waving protesters cheered as a flatbed truck with bullhorns, carrying the state's top labor leaders and the city's top political leaders, moved down Park Avenue. The Tuesday afternoon demonstration (June 13, 1989) culminated with the flatbed truck's arrival at Con Edison's headquarters where Local 1-2 office workers poured out of the building to join a boisterous rally. The next day, union members voted overwhelmingly to authorize a strike.

In addition to the human billboard, the campaign also organized mass distributions of leaflets at targeted banks. Contacts were established with the offices of those charged with voting the proxies for two large state public employee pension funds.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photos by Louis A. Nazario

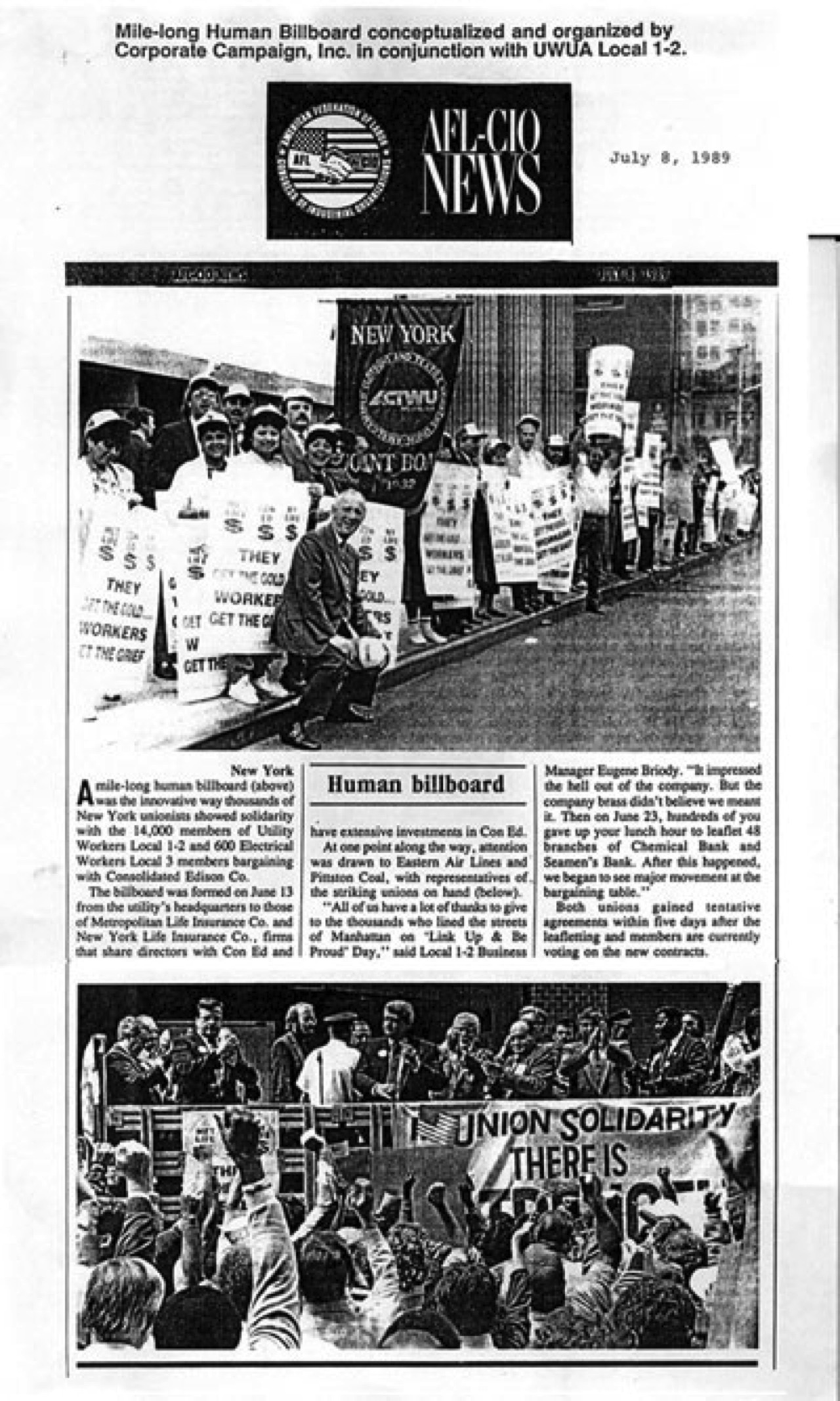

On July 8, 1989, the AFL-CIO News ran two large photos and an article on the demonstration. Local 1-2's business manager was quoted: "All of us have a lot of thanks to give to the thousands who lined the streets of Manhattan on 'Link Up and Be Proud Day,'.... It impressed the hell out of the company. But the company brass didn't believe we meant it. Then on June 23, hundreds of you gave up your lunch hour to leaflet 48 branches of Chemical Bank and Seamen's Bank. After this happened, we began to see major movement at the bargaining table." A contract settlement was reached and a strike was averted.